Due Monday 14th August by 12:00. 5 Weeks from Monday 10th July.

To formalise your plans for your research project and help you to effectively plan and map out the development of your research project over the next year of the course, complete an Illustrated Research Project Proposal. It should be an engaging and enthusiastic document that communicates both your passion and enthusiasm for your project, and its broader relevance and importance.

Your proposal will:

- Outline your plans for how you intend to develop your research project over the following three modules / study blocks, providing an indicative schedule of key activities and/or stages of the project.

- PHO740. Collaboration & Professional Locations. The module enables you to collaborate on creative projects and operate professionally within the creative industries. It aims to identify appropriate audiences and potential markets for the consumption of your practice.

- Good on paper

- SVP

- Long Table.

- Kel Portman and Deb Roberts. Walking the land.

- PHO720. Informing Context. The module aims to increase your understanding of critical contexts relating to visual culture and practices, allowing you to develop an informed and sophisticated contemporary photographic practice.

- PHO730. Sustainable Strategies. The module aims to expand your awareness of, and your ability to develop, effective strategies for the production, dissemination and consumption of your practice that are innovative, creative and sustainable.

- PHO740. Collaboration & Professional Locations. The module enables you to collaborate on creative projects and operate professionally within the creative industries. It aims to identify appropriate audiences and potential markets for the consumption of your practice.

- Define some of the objectives, concerns and themes of your research project, placing it within identifiable territories of contemporary photography and/or broader visual practices.

- Describe and analyse progress on the project to date.

- Communicate, using your own photographic work made during this module, suggestions of the visual strategies and methods you will be progressing in your research project.

- Detail any costs you will incur, and how you intend to meet these, as well as the resources and skills you anticipate you will need and how you intend to acquire them.

- Assess and analyse the limitations, risks and threats to the project, including ethical considerations, health and safety, and the environmental and ecological impact of your project.

Assignment Guidelines

- presented in a clear way

- impact and risk assessment

- potential partners – sponsors – council(!!). Evidence effort and (at the very least) intent. Tourist contacts? May be more professional to hold off rather than jump in and not make the most of an opportunity.

- LOOK AT THE GUIDE TO WRITING A PROPOSAL. It is generic but it does capture the essence of this assignment.

- Look at using Adobe Indesign.

- Break down assignment into components

- Prioritise on main body (assessments less important but don’t just do it a box ticking exercise)

- make use of academic support team – may be able to show them a draft.

Jesse’s comments. Your photos are key. Think of overall concern rather than goal. This part may or may not be used/related to the final project. Don’t fuss about getting details of modules 730 740 etc. the overviews should be enough. If you haven’t got photos then use the ones you have to point out why you wont be using them. They are interested in photos as research. If the number of illustrative photos isn’t much then make up with detail of research. They are looking for evidence to give marks. e.g. professionalism. Present in a PDF.

The Illustrated Research Project Proposal should also include:

- Bibliography of key critical resources relevant to your subject area. You may wish to subdivide into sources consulted to date and referred to in the text, and key resources you have identified and intend to scrutinise over the following modules. This should use Harvard style referencing.

- Appendices, including:

- Risk Assessment identifying the health and safety risks associated with a typical shoot or activity identified within your proposal. (Access Proforma on the Risk Assessment page of the PhotoHub. This is part of the Professional Practice section.)

- Impact Assessment Plan (See guidelines in the Impact Assessment Plan [MA] page of the PhotoHub. This is part of the Guides section.)

- Any other documents or material you believe is appropriate to support your proposal.

Appendices and Bibliography are not included in the word count.

Summative Assessment

This assignment will be assessed on the following course Learning Outcomes

| LO2 | Research | Determine appropriate research methods and methodologies to develop, produce, inform and critically underpin your creative practice. |

| LO7 | Professionalism | Produce work to a professional standard and model behaviours needed for success. |

Submission

Submit this assignment via Canvas as follows:

- You must submit your assignment in PDF format, maximum 50 Mb in size, maximum 1,500 words (excluding Appendices, Bibliography and Footnotes) via the module Assignment page in Canvas You will only be able to submit a PDF file. PDFs can be easily explored from MS Word or MS PowerPoint, but you are welcome to use more specialist design software if you wish.

Ideas

Localness refers to the quality or characteristic of being local, relating to a specific locality or community. It emphasizes the attributes, characteristics, or features that are associated with a particular place or region. Localness can refer to various aspects, such as local culture, traditions, businesses, products, or community engagement.

On the other hand, localism refers to a political or social ideology that prioritizes or advocates for the interests and autonomy of local communities or regions. It is a belief or movement that emphasizes decentralization of power, decision-making, and control, giving more authority to local authorities or residents. Localism often focuses on promoting self-reliance, local economic development, and community participation in decision-making processes.

While localness is a descriptive term that highlights the attributes of a locality, localism is an ideology or approach that seeks to empower and prioritize local communities. Localism is more politically and socially charged, often associated with efforts to protect local resources, economies, and cultures from the influence of external forces, such as globalization or centralization of power.

Creating the constraints

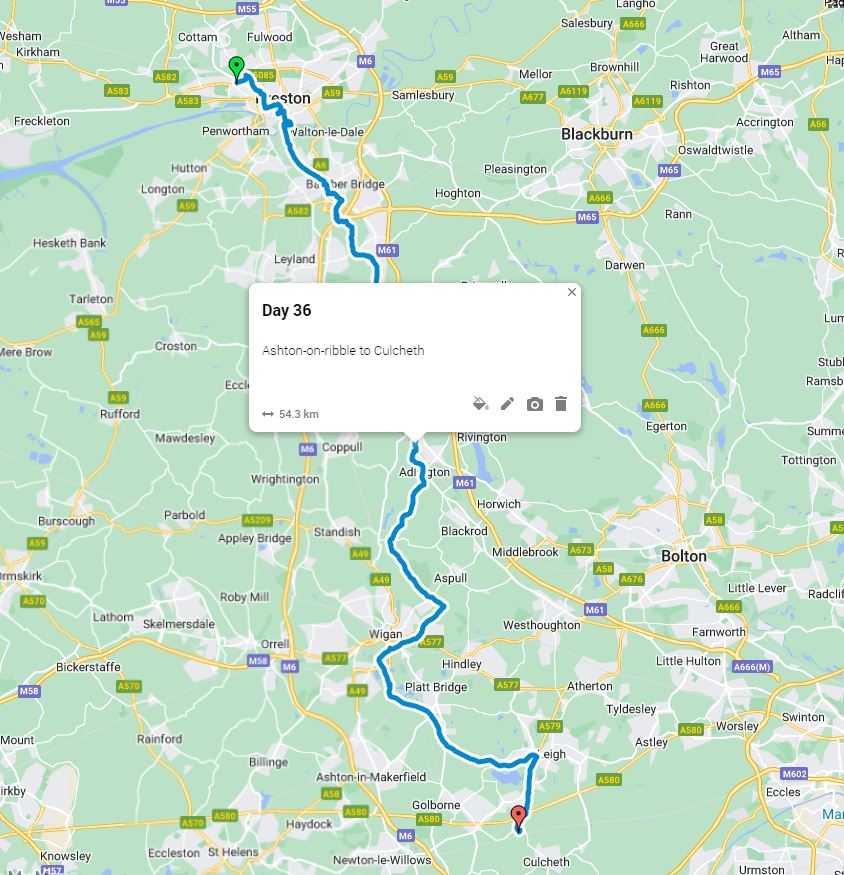

Q. What’s the furthest I have walked in on day?

A. 33.7 miles/54.3 km.

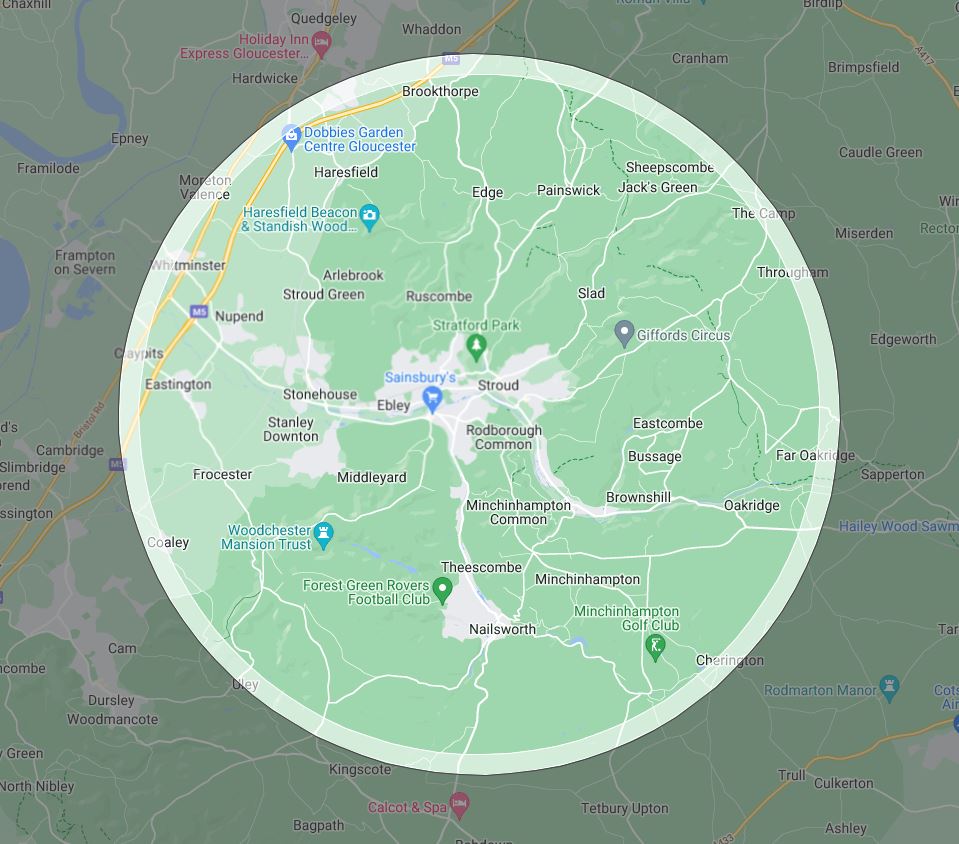

Q. If 33.7 miles was the circumference of circle, what would the radius be?

A. 5.36 miles.

Q. If I was to limit my world to 5.3 miles from my home, what would that look like?

It’s a small world.

- Creating arbitrary constraints but then sticking closely and accurately to the resulting concept.

- What kind of photos do I want to take?

- 5 miles from home – walking the perimeter. Around the world in .. a day.

- Exploring ideas of access to land – land ownership. Fay Godwin?

- Why 5 miles. Most I have ever walked in one day. 33.7 miles. = 5.36352 miles. [32.95 mapmywalk]

- Have rule about how close I need to be. Within 100 metres? Do I remain legal? Do I ask landowner’s permission?

- Circumference of the world 24,901 miles around equator. 3,963 miles radius. 12,450.5 miles to go half way around the world

- Circumference of the world 24,859 miles around the poles. 3,950 miles radius 12,429.5 miles to go half way around the world

- So:

- 1 Stroud mile represents 2,490.1/2,485.9 miles or using 5.36352 mile 2,321.3/2,317.4

- 2 Stroud mile represents 4,980.2/4,971.8 miles 4,642.7/4,634.8

- 3 Stroud mile represents 7,470.3/7,457.7 miles 6,964/6,952.2

- 4 Stroud mile represents 9,960.4/9,943.6 miles 9,285.3/9,269.7

- 5 Stroud mile represents 11,606.7/11,587.1

- David Bowie – 5 years on Ziggy Stardust – urgency of climate crisis

- A distance I can get there and back walking.

- Less than 5 miles from home

- First problem: a circle does not map onto a sphere.

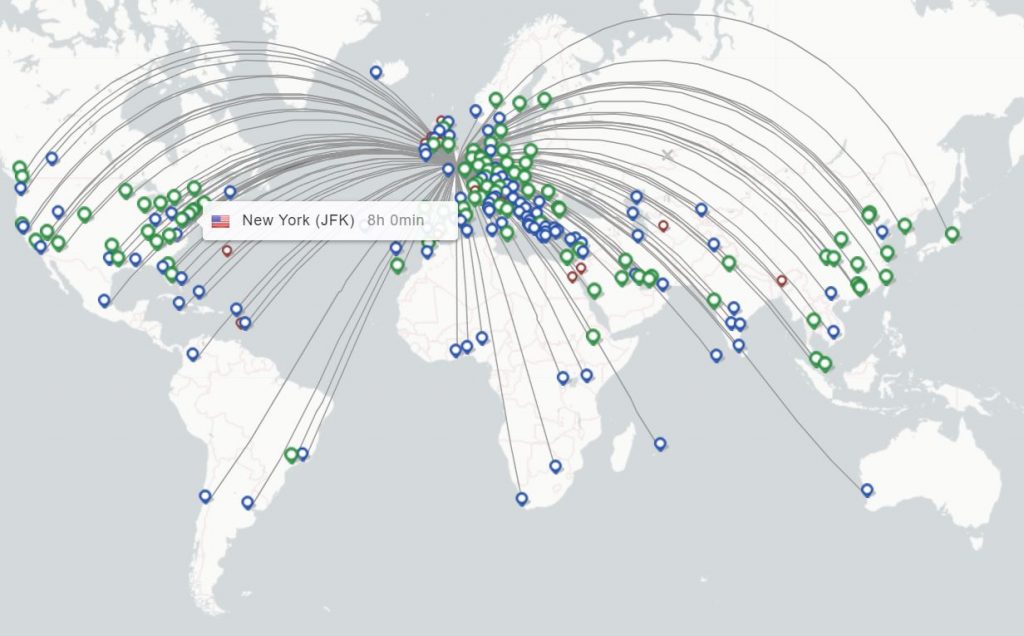

- mapping equivalent distance to places like New York, Taj Mahal, Everest

- “I’m going to New York today.”

- Could I do anything to jokingly make a reference to the proper destination – a cardboard statue of liberty.

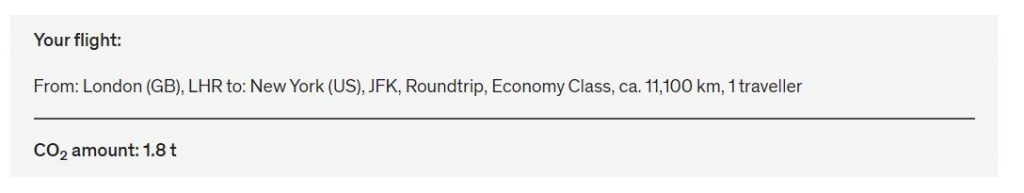

- Showing the carbon comparison for doing both journeys.

- Twinned with. As a title for the project. Comparing carbon costs

- Top 10 destinations. Compare with real-world destinations but also think about what are top 10 (worthy) destinations in Stroud area. Side-by-side photos.

- Landmarks – Incinerator, Stroud Brewery, Long Table, Food Hub, Land Trust, Micro Dairy, Canal (the Nile). Compare with landmarks in the real world.

- The flat earth society – early maps

- The Trueman Show. Walking the perimeter of Australian outback farm

- Carbon footprint of project

- walk

- electric bike

- Ludic photography

- Doing another version of the 5 mile map that just has iconic place markers on it.

- Like a good science fiction film, you suspend your disbelief but you still want the rules to be consistent.

- Getting suggestions from other people and using that a starting point. Immediately thinking of where they went – or would like to go – on holiday. What collaboration would then follow? Maybe they go on the walk as well.

- Recognising the difficulty of making the ‘right’ choices. You want the holiday, the new car, the latest fashions and the out-of-season food.

- Links

- https://www.latlong.net/countries.html

- https://www.mobilefish.com/services/distance_calculator/distance_calculator.php

- https://www.freemaptools.com/radius-from-uk-postcode.htm

- https://www.calcmaps.com/map-radius/

- https://theflatearthsociety.org/home/index.php/about-the-society/faq

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2020/02/24/weather-helps-disprove-flat-earth-hypothesis/

- http://www.movable-type.co.uk/scripts/latlong.html

- https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=1G-E6DujKQnQy1gF05tRapPcFpn8KUrU&ll=51.73229512829546%2C-2.2665397452107428&z=12

- https://maps.walkingclub.org.uk/admin/gloucestershire/stroud/parishes.html

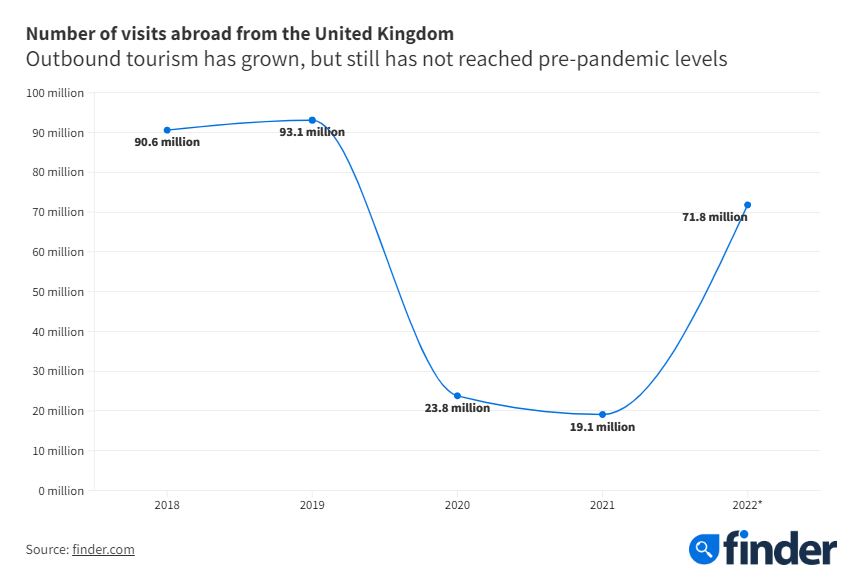

- https://www.finder.com/uk/outbound-tourism-statistics

- https://www.bl.uk/picturing-places/articles/landscape-and-place

- Destinations.

- New Work

- Dubai

- Hong Kong

- Everest

The following guidelines are designed to help you with specific assignments on the programme in mind, but also to provide you with a broader, general guide for future reference. You Research Project Proposal and Final Major Project Proposal assignments (MA students only) will not necessarily need to cover everything in the following guide.

First… the brief

As with any proposal, it is vital you are completely aware of any parameters set by whoever will assess or judge the proposal. If you are requested to submit in a particular format, or under a certain file size, then you must adhere to it exactly. It is easy to get carried away with your prose and drift away from the brief or guidelines that are set, so keep this close by and keep referring to it to check you are following guidelines correctly.

In a professional context, a proposal that does not follow guidelines exactly is likely to be rejected immediately.

1. Engage

All proposals have one thing in common: they should all attempt to engage the reader right from the outset. A proposal’s primary function is to grab the attention and spark the interest of the reader.

It’s important to identify what the key information is ie the relevance or importance of the project, and place this right at the beginning of the document. Never assume your reader will read your proposal at their leisure, or that it won’t be read alongside other proposals competing for the reader’s attention.

You will need to spend some time distilling this information, refining your pitch to make sure you are prioritising the necessary information.

In practice, it might be that at the beginning of your proposal you have a short summary containing this information, which you may also have prepared as copy to enter in an e-mail or covering letter to whoever it might be specifically addressing.

Whatever the form a proposal takes (printed document, short video, verbal pitch) it should be appealing: make it look nice.

2. Know your reader

Whilst it isn’t always possible, you need to be as aware as you possibly can be as to who is going to read the proposal, and make sure the tone and content is appropriate for your reader or, depending on the nature of the proposal, the audience.

What exactly you might be trying to get from the reader – such as financial or other support – will also have a bearing on what information you need to put across, and how you tone your prose or speech.

You need to bear in mind the complexities of the actual subject matter you might be dealing with: will the reader already have knowledge of the subject matter of your project? If not, how much information do they need to know, and how can you get it across? Or where can they find out more? You may wish to include footnotes, references and a bibliography.

3. Objectives

Any project will have research objectives, which define what you are trying to achieve. This is distinct from outcomes or outputs, which describe the final form(s) the project will take, such as an exhibition.

Research objectives might sound like a grandiose term, particularly when it feels like there are few subjects and topics that haven’t been explored photographically. It is really just about describing the themes and subjects present in your work or the project, and what you want to discover through your photography.

There is nothing wrong with modest research objectives, such as the creation of a very detailed study of a very specific subject. With that said, any activity should have a ‘point’ (or rather ‘objective’) and so you will need to articulate exactly why the project is, in your own view, necessary and relevant.

4. Context and critical background

How does the project fit into, or extend or develop, existing knowledge and discourses around the subject?

Whilst this might sound like an area that is only relevant to work made for gallery-going or academic audiences, another way to think about this is as a competition analysis: who else has made similar work or explored similar topics and / or subject? How will the project you undertake differ from, or build upon, what’s been done before?

Again, it’s possible here to reiterate the importance and relevance of the project and to generally convince the reader you know your subject and are well informed about the work of other practitioners.

5. Your practice

It’s important to assure the reader of your ability to fulfil your proposed goals by citing your achievements and successes to date. A snapshot of your professional achievements and activities gives an idea of who you are, and how the proposed project extends from prior work. Alternatively, you may wish to include relevant details of prior work and / or experience to support your ability to fulfil your proposal.

Taking the reader of your proposal into account, you may want to outline particular technical approaches in your proposed project or your practice more generally, such as techniques, processes and strategies. But this should be addressed with moderation – don’t waste time with verbose technicalities, and only discuss if it is particularly relevant to the research objectives or the theoretical underpinning of the work.

6. Audience: who is the project for?

If your project is worth making, then it is worth being seen.

It’s vital you can demonstrate an understanding of who the work is most relevant to, and how you will bring them to your work, or take your work to them.

If you are working editorially, there may be particular publications whose readers will most benefit from your story. If working commercially, this might mean showing an understanding of the exact demographic your work is trying to reach, and provide a brief sense of how this will be achieved through visual and other strategies.

In practice, a lot of contemporary photography is pursued and consumed by a specialist following of people, who support photographers by purchasing books, prints and attending talks and workshops. Consider how you can develop your position within this group, by getting involved and collaborating with any networks and regional development agencies for photography in your area, who might be able to help promote your project.

7. Outreach: engaging new audiences

Generally speaking, the more people that will see a piece of work, the more likely it’s going to be that an organisation will fund it, especially in relation to funding from public bodies, such as the Arts Council, EnglandLinks to an external site. who are paid for by the Lottery and taxpayers. A project’s ability to engage with new, particularly non-specialist and marginalised, audiences are given great importance when it comes to decisions on awarding grants.

Depending of course on the detail of for whom your proposal is written and why, it may be very important to explain how you plan to engage with groups that are less involved in the consumption of the arts; typically people who are younger, older and / or less well off.

When it comes to the resolution of your project and its publication, social media is likely to play a key part in your campaign to publicise your work. If you have a blog or any other social media platform dedicated to the project (Facebook page, Instagram account), it is a good idea to include this information so the reader can get a sense of the project from the position of a member of this new audience.

8. Financing and funding

This is one of the key pieces of information for somebody reading a proposal who might be in a position to offer financial support for your project, or commission it outright. In financial terms, a proposal is more of an estimate than quote. It’s important to demonstrate a realistic awareness of the costs involved in a project and outline how you will meet these, or where the gaps are in your budget that you are looking to fill.

Try to take account of significant costs involved including travel, equipment hire, insurance, meals and accommodation, film / processing / scanning, studio hire, other staff (assistants, models, translators, guides…).

Funding creative projects through grants and sponsorship is notoriously challenging. Also, many organisations will not fund projects that are being made as part of an educational programme. However, it is worth familiarising yourself with some sources of funding, such as the Arts Council’s list of other sources of fundingLinks to an external site..

9. How much are you worth?

Although probably not appropriate in the context of this assignment, you should take this opportunity to calculate what you consider to be a fair daily rate for your services as a photographer. There are many ways to do this, and some professional bodies, such as the National Union of Journalists publish guidelines for daily ratesLinks to an external site..

It is therefore difficult to guide you specifically but the following points should help you to think about a daily rate you and your clients will be comfortable with:

- Usage: your rate should reflect the way in which your photographs will be used. Are you licensing the use of your photographs for a short period or for longer? Is it worldwide or regional? Look at the Association of Photographer’s Usage CalculatorLinks to an external site..

- Stock equivalent: are the kind of photographs you’re going to take for a client available from an agency or stock website? If so, what would it cost the client to buy all of these individually?

- Overheads: your daily rate should include your premium as a freelancer, that factors in the running costs of your business, your overheads, pensions, and maternity / paternity leave, holiday pay and sick leave.

- Tools: your rate should take into account the high costs of professional photographic equipment. You also need to consider the rapid depreciation in value of equipment. To get a sense of the per-day value of the contents of your camera bag, look at professional hire rates and see what it would cost to equip someone with a similar array of tools. Inexperienced photographers often charge less for a day rate than their equipment might be earning by itself.

10. Other resources and skills

Don’t be afraid to identify where the gaps are in your knowledge base or skillset. Outline how and where (if necessary) you will acquire any further training or tuition and again, how this will be met financially. The reader will gain more confidence in your awareness of your limitations, rather than your naivety in your abilities!

11. Collaboration and partnerships

In practice, it is likely you will self-fund the costs of your research project. However, institutions and organisations who are in positions to support projects generally won’t fund the entirety of a project and like to know money is coming in from elsewhere.

The chances for success of a project are generally greater when there are more people and organisations involved, to share networks and promote the projects and its activities. Therefore, it’s important to identify what other individuals or groups are involved in the project and how they might contribute to its success.

If you are working with other professionals (e.g. designers, stylists, writers, curators) you should identify them (and briefly qualify their success) and importantly, include their costs. It may be they are providing their services for free (or you are trading your skills for theirs somehow). If this is the case, it’s important to include this in your budget as payment in kind, as an amount towards which a potential funder might match.

12. Time scales

Use a proposal to plan out the different stages of your project and place realistic targets and goals in place to sustain the momentum of the project.

It is unlikely you can be certain of exactly what you will do in a particular week several months in the future, but it’s important to set deadlines as to what you hope to achieve by what point.

Production is involved in any project (even if it is just the production of a digital portfolio) so it is good to set a deadline for when something is due and work backwards from there, allowing yourself plenty of time to buffer any potential delays.

13. Risk

Are there any risks associated with the activities you will be undertaking? These might be to your own health and safety, those with whom you are collaborating, or your subjects. Or to your own equipment or other people’s property. If you are planning to work in a hazardous environment of any kind, what training will you need to minimise risk, or what courses / qualifications have you already undertaken?

‘Risk’ can also refer to the ethical dimensions of a project. What do you need to be sensitive and mindful of in elation to your subject, practice and methodologies? Is there a danger of, at best, upsetting someone or, at worst, having legal action taking against you? If you are photographing people you should consider obtaining Model Release forms. If you are photographing children, young adults or other vulnerable groups of people you must detail how you will secure their consent.

If you don’t already have it, now is a good time to purchase insurance for your equipment, personal liability and perhaps professional indemnity insurance as well.

Please note: You must accompany your Illustrated Research Project Proposal [PHO710] and Major Project Proposal [PHO750] assignments with a completed Risk Assessment Form.

14. Outcome

Although it is not the case in this assignment, a proposal will generally have a specific outcome, or output, in mind (many proposals tend to be for a particular output, such as an exhibition). However, if you have got ideas as to how you might realistically resolve and publish your work, then you should provide some brief details.

15. Qualify success

The reader will want to know how you will measure whether the project is successful or not. If the proposal is for a commercial shoot, then success might translate as increased sales or an enhanced profile of a business or organisation, perhaps quantified by increased traffic through their social media channels.

An organisation who might support a project will want to know whether the project has achieved its goals, such as having been seen by a certain number of viewers / visitors, or generating an amount of revenue.

Whatever the case, you should think realistically about what success will look like in terms of a completed project, and what ways you will qualify this, gather feedback on the project and take your practice forward.

Nature is a site in which tourists indulge their dreams of mastery over the earth; of being adventure heroes starring in their own movies. In this way they are showing not only their adventurous and indomitable spirit in the face of (supervised, safe, tourist-orientated) daring experiences; they are also showing off their skills and talents as sophisticated consumers of travel, the major leisure commodity of the late twentieth century. These adventures within nature will become part of their own travel narratives, their own self-constructed illustrated autobiographies.

Bell, Claudia & Lyall, John. (2002). The Accelerated Sublime: Thrill-Seeking Adventure Heroes in the Commodified Landscape. 10.1515/9780857457134-007.

Bell, C. and Lyall, J. (2002) ‘The accelerated sublime: thrill-seeking adventure heroes in the commodified landscape’, in S. Coleman and M. Crang (eds), Tourism: Between Place and Performance . New York: Berghahn. pp. 21–37.

[Urry, John/Larsen, Jonas]